Why Vox Media is hedging its bets in ad tech and data

Everyone's rushing to grab email addresses - but not everyone wants to share

I asked a very naïve question the other day on my Next in Marketing podcast.

I was talking to Vox Media Chief Revenue Officer Ryan Pauley about how his company plans to navigate the post-cookie world - where winning – if not surviving – will be dependent on how much first party data you can snatch up.

Companies like the New York Times, or Bloomberg, for whome it’s very natural to ask readers to create a log-in as part of becoming a subscriber, seem to be in a great spot. But everybody else? I asked Ryan how Vox is handing this transition, when presumably most people aren’t willing to create an account to read The Verge or Vox.com or SB Nation.

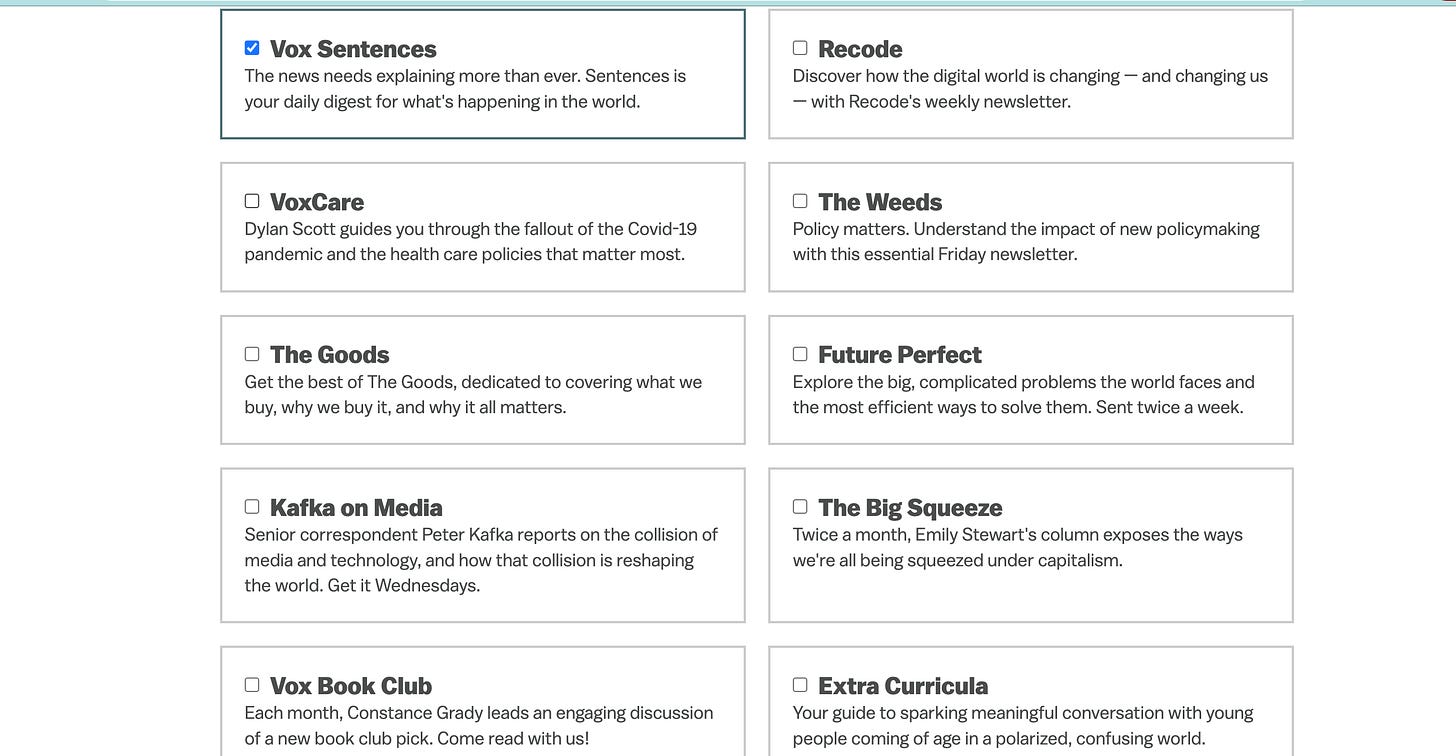

Duh, said Ryan. We have New York Magazine for starters. Plus, we have loads of newsletters.

Ok, so Ryan was actually nicer in his response– he didn’t actually say ‘duh.’ But I should know better that of course, everybody who matters has an email plan. In fact, Vox has A LOT of newsletters. In fact, I get Peter Kafka’s fantastic media one each week. New York Magazine has 25 alone. Thrillist, Eater, the (email) list goes on.

What I’m not clear on is whether Vox mixes in my email address with all the others that are being collected and pooled together by the Trade Desk-backed UID 2.0. I have no reason to believe Vox is being cavalier about all these lists.

That said, does anybody know if their email address is in the UID 2.0 list?

To be sure, Vox is testing using UID 2.0 as part of a new Trade Desk partnership. You can bring in that data to find matches through Vox’s own first party data mechanism - Forte- but Vox’s data doesn’t leave the garden.

Indeed, Pauley was quick to note that the company isn’t all in UID 2.0 as a cookie replacement. Nor are most marketers.

When it comes to all these cookie alternatives, “we are participating and observing,” he said. “We will serve what the marketing community seems to coalesce around.”

“That’s an unanswered question right now,” he added.

Still the mission to collect as many emails addresses moves forward, unabated, across the industry, among publishers and brands. Try getting a sale price, or even using a brand’s app, without forking it over. Mostly, I don’t think much of it. Does anybody read the fine print when they share their email?

Right now, ad tech companies are just trying to prep for the cookiepocalypse while simultaneously to get through Apple-hell, by amassing as many ‘HEMS’ as possible. HEMS are hashed email addresses, the supposedly breach-safe, supposedly totally consentually-acquired asset that is becoming the industry’ crypto. HEMS are going to power every aspect of digital advertising maybe, as long as no one takes away their value.

But as Cafe Media’s Paul Bannister noted recently, there is a potential of consumer pushback to HEMS (led by some big tech companies with agendas).

We’ll see. In the meantime, I wonder about what happens when FTC chief Lina Kahn starts asking about HEMS. Her team just went after a rather obscure ad tech company, Kochava, about its use, or ‘sale’ of location data. To be sure, Kochava ended up in the FTC’s cross hairs because of its connection to abortion clinic location data – which is understandable. But lots of companies are using location data– which is often connected to HEMS.

What happens when the FTC starts asking more questions about this? Worse, what happens when something goes wrong? I’m far from an expert on encryption, but one thing I’ve noticed in life - shit always gets leaked or hacked. And things go wrong in tech, even with the best of intentions.

I’m nearly through Mark Bergen’s fantastic new book on the history of YouTube (seriously, buy it). If there’s one recurring theme, it’s big tech executives- usually low IQ software geniuses, naively trust the idea that scaled tech will fix all problems, and then end up shocked when they don’t.

Ad tech and mar tech companies seem very comfortable with all this collecting and hoarding of emails. Some of these executives are similar in their philosophy to the overly-idealistic ones at Google. But others are more of the ‘don’t worry and don’t ask too many questions’ variety.

I could be making too much of this - after all, emails aren’t credit card numbers or social security data. It’s not as though companies don’t send me emails I don’t want. Then again, the promise of HEMs is that they can be theoretically connected to all of a person’s devices, and even all the places they go.

Am I being wishy washy about this? I’m not sure. Regardless, please subscribe.

In the meantime, please do check out my terrific conversation with Vox’s Pauley. Some other highlights:

Brands still believe in the power of content, but the market is going to take a hit. Adweek’s Mark Stenberg noted that part of the reason that Bustle decided to shut down several pubs was due to branded content spending falling off a cliff. Vox has tried to create as many repeatable executions. “Typically what markets look for in moments like this is speed of execution, and addressable inventory,” said Pauley. “Tactics that can be directly measured.”

Publisher-built ad tech can work, but it needs to be special. Vox rolled out Concert, its proprietary marketplace, back in 2016 with big partners like NBCU. Unlike most every cross industry consortium, it’s still here. Pauley said that Concert now has 500 advertisers running distinct creative with over 50 publishers, and the company has now just built’s own SSP. When Pauley brought this plan up to industry executives, they told him, “Why the hell would [you] do that?… It’s a good idea but good luck.”

Great conversation among two highly respected friends. I am skeptical on the sustainability of HEMS for the reasons cited in the article. I think the industry is embracing them like people clinging to an umbrella in a thunderstorm; that umbrella is going to invert and end up blowing away in the wind. For now, anxious investors and nervous advertisers are holding on with one hand while they sift through more durable alternatives. Whatever we ultimately coalesce around will need to be consent first, transparent, auditable and give clear and immediate control to the consumer so that they can change their choices instantly and with ease. Much will have to change to get to those standards, but until we get there, we’re just praying the umbrella will survive a storm where the wind is building.