Nielsen is All In on Big Data - Except in One Key Way

Plus Ari Paparo on why it took so long for regulators to recognize the Google monopoly

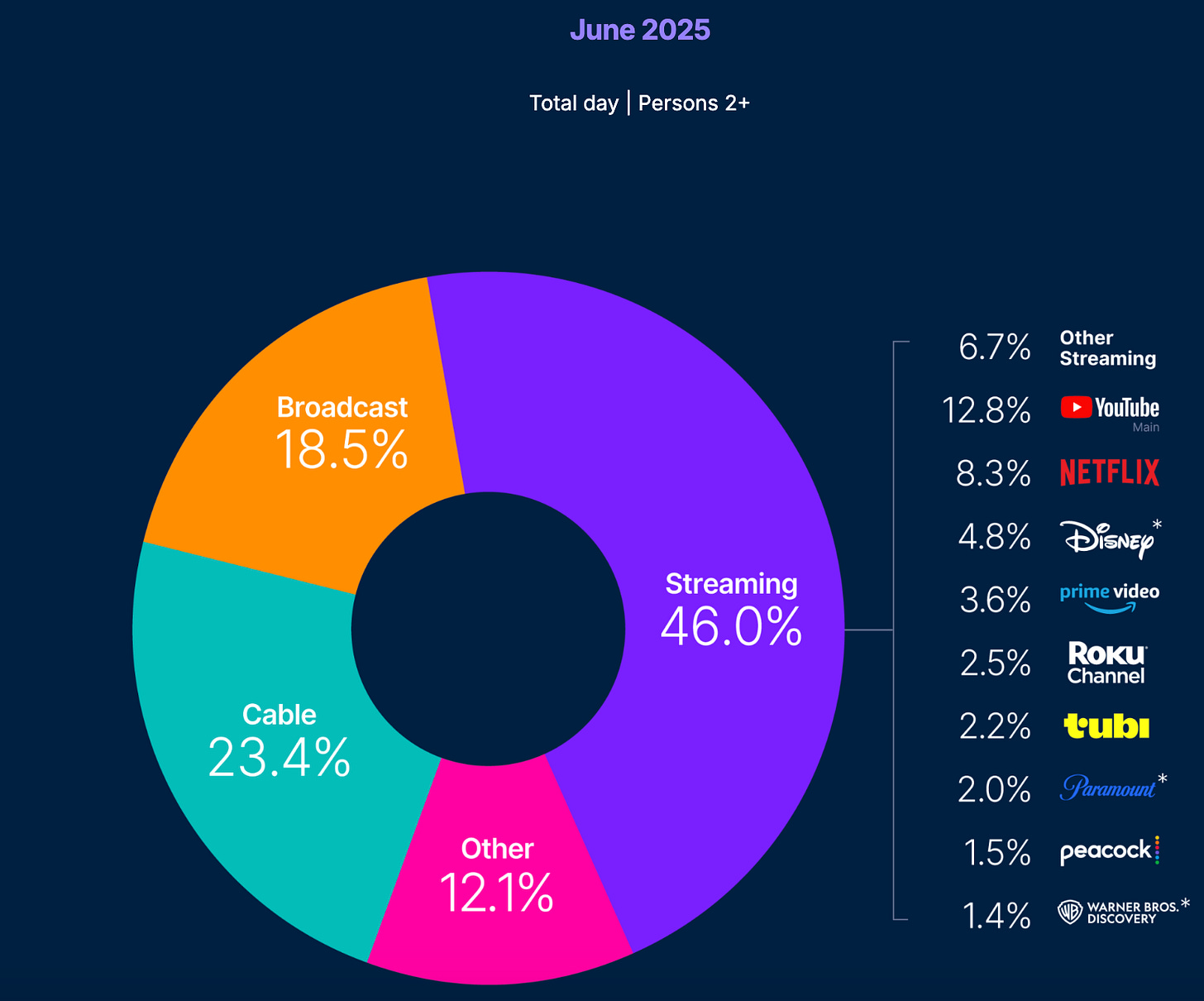

Putting aside AI (if you can) - perhaps nothing has shaken up the media and ad industries over the past few years as the rise of YouTube on television.

As you likely know, Nielsen says that YouTube now accounts for upwards of 12% of all TV viewing, which is up from the then eye-popping 9.9% figure recorded a year ago.

That growth - particularly in light of the anemic share generated by many media giants (and even flat numbers at streaming king Netflix) - has shaken up Hollywood, Silicon Valley and Madison Avenue. It has brought more awareness to, and legitimized creators, and forced many executives to rethink how they program to, and market to, young generations. It’s even led more than a few to ask the question - what exactly is TV?

Did you know that data comes from a panel of 40,000 American homes?

Media buying today? Complicated. Fragmented. Risky.

That’s why EX․CO created Mastering the Multiscreen Mix—a field-tested playbook built for brands and agencies who want to make better decisions across screens. Learn where the waste is, what actually works, and how to maximize your ROI across CTV, DOOH, and digital video. It’s your cheat code for the multiscreen world—get the guide now.

It surprised me, given that over the past several years, as Nielsen has faced pressure from a new breed of ‘alternative’ measurement companies touting ‘real’ TV viewership, the company has moved to reinvent its TV research model. The new Nielsen One platform - which saw the Ads version of the product go live in early 2023, followed by the still in alpha ‘content’ version later that year, promises to blend the best of Nielsen’s panel prowess with ‘Big Data.’

In pushing back against new measurement upstarts, Nielsen’s stance has been that Nielsen One pulls together the most advanced forms of TV show/ad viewership tracking - i.e. data pulled directly from smart TV screens - with hand-selected, demographically-representative panels so that advertisers and programmers can still understand what kinds of people are watching shows and services.

This pivot has mostly worked quite well, as the so-called ‘currency wars’ have cooled, while Nielsen keeps renewing larger deals with major media companies.

That Big Data Pivot, however, doesn’t apply to The Gauge - which is the product of data pulled together by Nielsen’s roughly 40,000 household panel, including 25,000 homes employing a specific “streaming meter.”

In fact, when The Gauge started a few years ago, it pulled data from just 5,000 streaming meters.

Does this matter? It feels at least noteworthy (if not counter intuitive), given how much traction and attention The Gauge has generated over the past few years. As one ad executive put it - “it shapes discourse quite a bit.” The Wall Street Journal framed it as evidence that “Hollywood is losing ground.”

At least one top ad buyer I spoke to at Cannes thinks this is a big deal - how could you not use ACR data (audio content recognition data) to track the impact of streaming, Netflix, YouTube, etc. when you have so much more of it at scale? Don’t we want ‘real numbers,’ not projections?

It's worth noting that while Nielsen does source ACR data for its Big Data + Panel product from outside vendors, that data is focused on linear and cable viewing data pulled from smart TVs and set-top boxes. In the case of ACR, data from set-top boxes would not be useful for tracking streaming apps like Netflix.

However, the research company does utilize a proprietary audio signaturing approach (another form of ACR) to measure streaming program viewing in its national panel. The key benefit here is that it utilizes the existing metering infrastructure, which also provides accurate, person’s level measurement for streaming programs.

To be sure, it’s not as though individual media buyers or advertisers plan or buy campaigns strictly using The Gauge data. These companies often employ their own planning tools, and negotiate buys with specific sets of currencies. Not to mention how often brands are evaluating media buys in terms of specific outcomes these days.

But, then again, The Gauge surely impacts macro budgeting decisions. Should we be doing more with creators? Is so and so streaming service a failure because it barely shows up on The Gauge?

I personally wonder if YouTube and Netflix could actually be undercounted here. Who knows?

Ironically, it’s not as though Nielsen can’t employ ACR data to track streaming. The company does incorporate this information when it releases its top ten streaming show lists. In that case, Nielsen utilizes specific show signatures from its partners. Apparently it’s easy enough for ACR data to see that “Stranger Things” is on- but a show like say “Brooklyn 99” could be on Netflix, or Hulu, or live cable.

Thus, as of now, ACR data is not being used to track app-level streaming, but it could be part of The Gauge down the road.

Prominent Book Author Ari Paparo on Whether the Feds Took Too Long to Nail Google

As you may have heard, ad tech veteran and Marketecture CEO Ari Paparo has a new book coming out on August 5: Yield: How Google Bought, Built, and Bullied Its Way to Advertising Dominance

I had Ari on my podcast this week to talk about why he took this subject on, and how he went about writing a book about a world he was right in the middle of.

My biggest overarching question in reading Yield (and following the entire Google anti-trust story) was: how did regulators not see this and stop this monopoly way sooner? After all (hindsight being 2020), how could you let a dominant seller of digital advertising also own a supposedly neutral marketplace, as well as key tools used by both sides of the industry?

“I don't think it was preordained that they would be this absolutely dominant. Or it wasn't also preordained that programmatic was going to become this dominant, that it was going to effectively become the lingua franca of all of digital advertising. But it all did happen. It did roll out that way. And it turned out to be sort of a winner-take-all market to some extent.”

“I think a lot of the problems that Google started running into in the second half of the 2010s that led to the antitrust was about a changing of the guard where…all these folks who basically built the display business at Google moved on to other career opportunities…and they were replaced by people who came from search. And the people who came from search were pretty arrogant about the business.”

I also asked Ari whether we are seeing history repeat itself, and if any regulators can be expected to have a real handle on AI-driven advertising

“I think there's definitely a danger that Amazon uses its power, which is extraordinary. It's an extraordinary amount of data for marketers and reach among its audience to tie up a big portion of the media business and create a little mini monopoly. And I don't see anything stopping them right now because what they're doing is not illegal. They don't have a monopoly in anything except maybe book sales or something.”

Regarding AI “It's probably the right thing to do to look into that right now before it gets out of hand. I don't know what the right remedy is.”

Take a listen. And buy the book.